Car woz here.

The request was polite but firm. It didn’t feel like it left any room for negotiation. “Can you move your car please? This is where I park my car. I live across the road.”

A friend was dropping me home. We were parked temporarily on the street, outside my house, saying our farewells.

There’s a word I’m looking for…entitlement. The entitlement that a motorist in a car-centric city gets to experience. “That’s my parking space.” Really?

Until recently, there were a handful of high school students riding their bikes to the nearby high school. I used to see them on the bridge on my way to work each day. I hadn’t seen them for a while. I was curious. Yep. You guessed it. They had turned 16. They were driving now. To school. Driving at every available opportunity, I suspect.

There’s a word I’m looking for…aspiration. The aspiration of a teenager growing up in a car-centric city seeking to join the motoring elite. “It’s better going by car.” Really?

Meanwhile, in a parallel universe.

I get the feeling that the separated cycle path is being touted as the ‘silver bullet’ to get more people cycling. “Build them and they will come”, we are told. But is it really that simple? Sure, the off-road path I use has enhanced my daily cycling experience. Yet, I find it hard to ignore the reality that I see and hear everyday. I’m not suggesting that we should not aspire to build a network of cycle paths but I do have some questions and concerns about this approach. It’s not like I haven’t argued this before. It’s the raison d’etre of this site. But I saw something recently that inspired me to try again.

I’ve been enjoying the stories and insights coming from the Modacity family bicycle adventure to The Netherlands. For those of you who are unfamiliar, The Netherlands is the gold standard of city cycling. The Dutch have very high rates of everyday cycling. So of course, we turn to Dutch cities to see how they have achieved it. And what do we see? Young and old, male and female, riding slowly, dressed for their destination, on (you guessed it), separated cycle paths. “Eureka! That’s the solution”, we hear. “Build them and they will come.” But back up the cargo bike a moment will ya.

Because check this out…

- A cycling utopia is created by demand rather than design.

- The Netherlands is a story of traffic calming rather than of bike lanes.

Say what? I mean, the intuitive response would be to say that the separated cycle paths caused the increase in numbers of people cycling. But according to Modacity, the separated cycle paths came about as a result of more people cycling. They were built as a way to manage the numbers. They were built as a consequence of lots of people already cycling. A mandate to protect people on bikes existed already. A process of traffic calming was already well established. Cycling was already a normal daily activity. That fight had already been fought and won. A fight that has barely started in most other cities.

That’s not to say that building a separated cycle path will not act as an inducement to get people out of cars and onto bikes but…that’s only a part of the story. Of course it would be really great if that approach was the shortcut to a cycling nirvana. It would be great. But in the meanwhile I want to suggest that we reframe the conversation. Let’s move beyond just talking about infrastructure and instead, start talking about building demand for cycling. Because that would open up the possibility to engage in a wide range of push and pull strategies. Making driving less desirable needs to be on the agenda. Building demand for cycling needs to be approached in all sorts of marketing, policy and infrastructure ways. Push and pull. I know my life would be made easier if the issue of rat-running was taken seriously.

I can see the problem. Campaigning for separated cycle paths is relatively straight forward. Relatively. Compared to asking a motorist to address his/her sense of entitlement, that is. But that’s what it’s going to take. If we are serious about rescuing our cities. Getting people out of cars and onto bikes needs to be seen as being about behaviour change. Trying to create a cyclised city by building cycle paths alone is the equivalent of trying to make an omelette without breaking any eggs. At the moment we have a top down approach. There is minimal community engagement. And the engagement that does exist, is premised on a high level of tolerance and acceptance of the current dominant role of motordom in our cities.

It concerns me that what seems to be ‘driving’ cycling advocacy at present is expertise in designing bike paths. I propose that knowing how to design bicycle infrastructure should not equate with knowing how to get more people riding bicycles. Nor is getting people riding bikes a ‘chicken/egg’ conundrum, as I sometimes see it being presented as. There are a huge range of steps that could be taken to get things moving along faster. Just ask. Similarly, advocacy should not equate to knowing all the answers. And nor should it be acting as a barrier to progress. It should be a conduit for building demand.

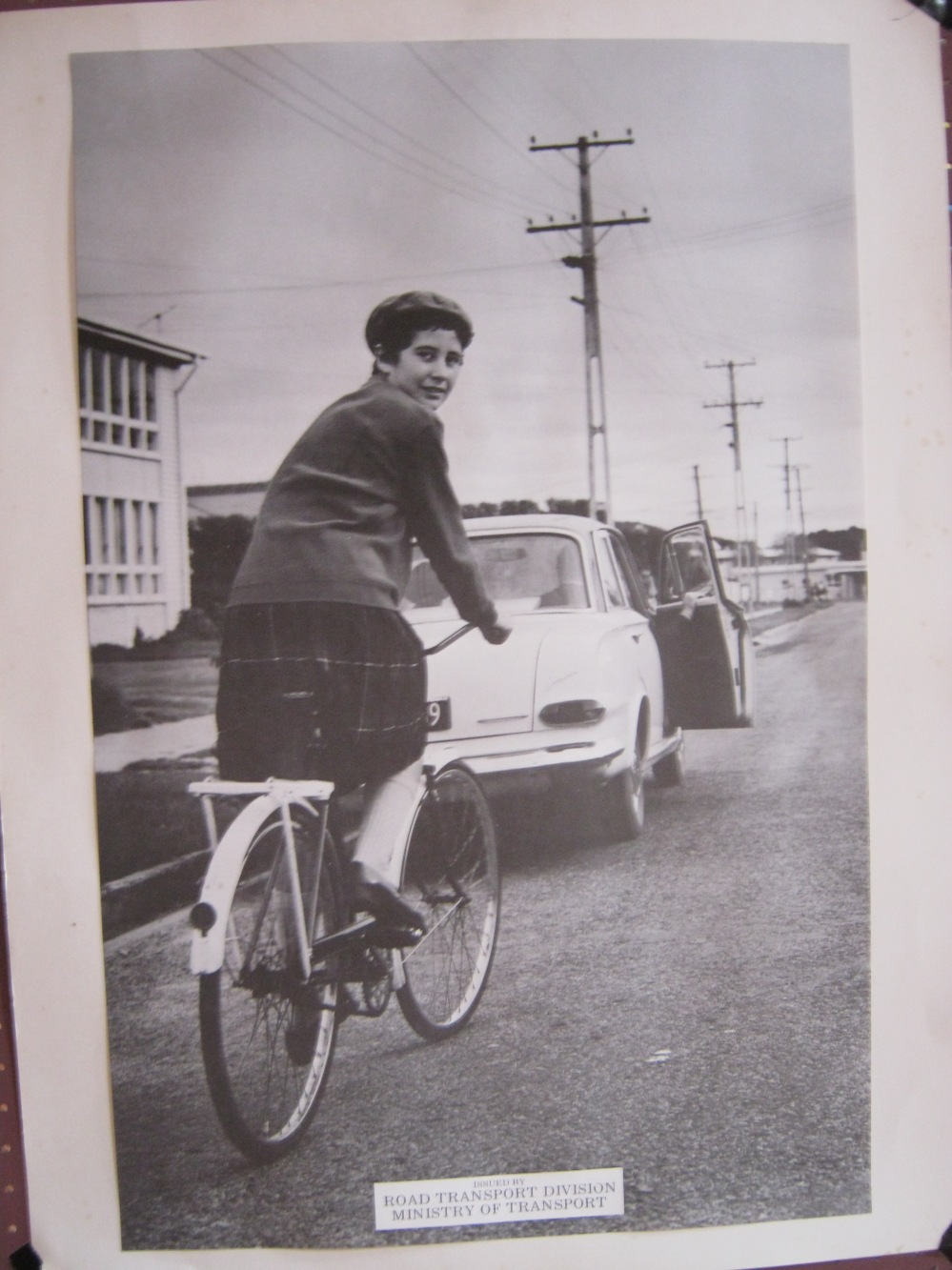

Finally, I propose that we adopt a new catch-cry. “Make it safe and pleasant and they will come.” That will offer up the possibility of whole new range of ways of engaging with the task at hand. To build that demand. To get the public, the policy makers and the politicians to sit up and take notice. I also think there may be an unintended consequence of putting all the emphasis on the “build it and they will come” approach. It could be that people really won’t ride bicycles until the city has a network of cycle paths. Which would be a shame because there is a lot of potential to put all those under utilised bicycles, parked up in the garage, to use right now. And the obvious presence of people on bicycles will generate the essential ingredient of demand. Which would, in turn, lead to those highly prized bike paths being built sooner than later. Which also reminds me why the image of the entirely ‘doable’ wheeled pedestrian style cycling, (as opposed to the image of the familiar hardcore cyclist), needs to be promoted much more generously.

‘Cycling’ is sport and recreation. ‘Riding a bicycle’ is everyday activity. No sweat.

Get involved via: Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, or Instagram.